Potatoes and Terroir

In the blood of all artisan farmers is an understanding of terroir, the concept that food possesses identifiable qualities that can be linked to where it is grown. Just as local grasses lend subtle flavors to a cheese, and climate and soil provide unique properties to a wine, terroir is expressed in every food. But most of us aren’t aware of this; commercial processing and globalization of ingredients has removed the locale from all but the few artisanal foods and farmers’ markets we have access too.

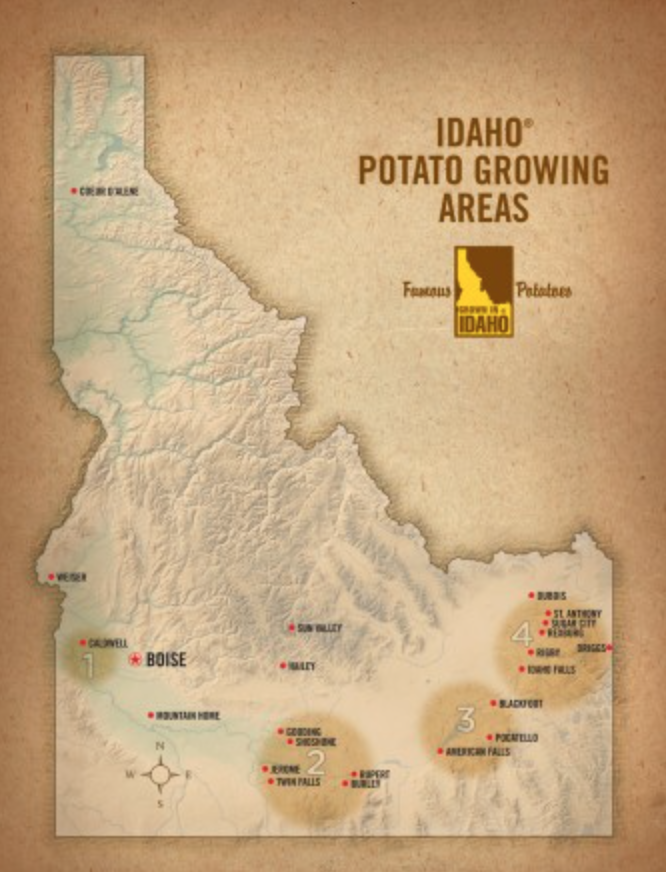

As a young boy in Idaho, locally grown and raised products were all we had. My family had a small farm located on the western rim of the Magic Valley potato-growing region where we grew dry beans, as our soils were better for beans than for potatoes. Other family members, east of us, grew potatoes. By the time I was eight years old I could distinguish between the beans we grew and those grown farther north. I believed I could also identify potatoes grown in Pocatello from those grown in Burley or Caldwell.

The ability to identify potato terroir seemed a common trait among Idaho farmers. One time, at the wedding of a high school friend held on the East Coast, I overheard the groom’s father loudly complaining that the restaurant should be serving Idaho potatoes rather than the ones from Oregon he insisted were on his plate. Many doubted his claims, especially given the amounts of butter, sour cream, and chives he had on his baker. Yet, at the end of the meal, his sense of terroir stood confirmed by the maître d,’ who admitted that, indeed, the potatoes were from Eastern Oregon!

Blight in a single variety of potato, the Lumper, resulted in the famine that drove my family from Ireland in 1848. Driven almost to extinction, the Lumper survived only in a few seed banks, an obscure reminder of the Irish tragedy. Now, however, I am heartened to learn that a few hardy growers are replanting the Lumper, driven by a desire to rediscover a cultural identity through food.

We are realizing that food and drink provide more than sustenance. With the right preparation and ingredients, a meal can connect us with our past, and awaken a sense of belonging to something greater than ourselves. Our growing awareness of the transcendent powers of food and drink in part explains the rise in movements like Slow Foods, and our current excitement over old recipes and heirloom ingredients.

Someday, I hope to visit Ireland and have a traditional dish of Colcannon or Champ made with Lumpers. Until then, I will continue to enjoy a traditional dish of Idaho mashed from a recipe handed down in my family for several generations. The secret to this recipe is to boil the potatoes in an herbal infusion of Rosemary and garlic that you make in advance. You can use this method to add subtle flavors to the potatoes, and even develop a few family traditions of your own.