Tartrate Stability – A New Approach on the Horizon

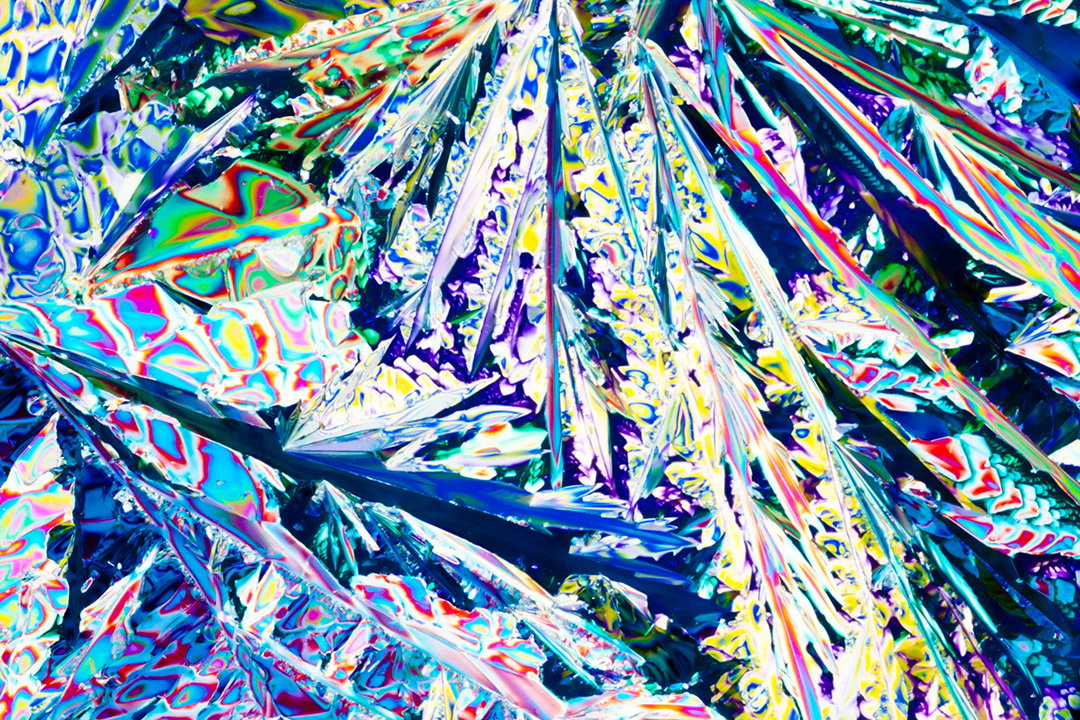

Tartrates are potassium salts of tartaric acid that occur naturally in wine. With storage, especially at a cold temperature, these tartrates can grow in size until they become large enough to precipitate out of solution. In a white wine, these precipitates form clear crystals at the bottom of the bottle. Consumers can be frightened by these crystals since they look like broken glass.

There are three approaches winemakers can use to deal with tartrates: ignore them, remove them, or add something to inhibit their precipitation. In 2015, we chose to ignore them. Though the resulting wines were beautiful, among the highest rated wines in Livermore Valley that year, we had to hand-sell them from our tasting room. We couldn’t wholesale the wines because, in a grocery store, no one is around to explain the reasons for the little crystals in the wine.

At least for us, ignoring tartrates is no longer an option. That is why we have returned to removing them. In factory wineries, tartrate removal can be done by passing the wine through a cation exchange resin (like a water softener for tartrates). In craft wineries, like ours, we chill the wine at 28° for a period of time. With chilling, the tartrates fall out of solution. Then, the wine is racked and bottled.

There’re two drawbacks with chill stabilizing. First, it is a huge contributor to our carbon footprint since it requires a large amount of energy to refrigerate the wine. Second, if not careful, refrigeration exposes the wine to oxidative stress. Now you can see my dislike of cold stabilizing. For a procedure that is only of cosmetic benefit, I can’t help but think that cold stabilization is an unnecessary step in winemaking practice.

An approach that uses less energy than the chill method is the use of additives that inhibit crystallization. There are several compounds approved for this use, but all of them have their problems. With no exception, additives like carboxymethyl cellulose or Arabic gum alter the texture of the wine from what the vineyard expresses naturally. Furthermore, these additives affect our ability to filter the wine, which might lead to the need to add sterilizing compounds at bottling. This approach is not an acceptable option for us.

Preparing for my spring class in winemaking at Las Positas College, I looked to see if there were any new solutions to the problem of tartrate stability in wine. That is when I came upon a research paper by Antonella Boso describing the use of an amino acid salt, potassium polyaspartate, for inhibiting tartrate precipitation. Though the safety of potassium polyaspartate is well demonstrated, what remained unknown was its effectiveness as a tartrate inhibitor in wine. Boso’s research, along with other studies, demonstrated that potassium polyaspartate prevents precipitation, and does not affect color, aroma, mouthfeel, or taste. An added benefit is that it has no effect on filterability.

As of this year, potassium polyaspartate has been approved in the United States and Europe as an additive for tartrate stabilization in wine. We are examining it closely. It is too late for this year since our white wines are already in the bottle. Nevertheless, this additive might be something we consider next year as we continue to reduce our carbon footprint.

_______________________

A Boso, et al., 2015. Use of polyaspartate as inhibitor of tartaric precipitations in wine. Journal of Food Chemistry, 185: 1-6.